|

by: Lynne Warren August, it's that time of year. Invasive jumping worms (IJW)are grown up, plentiful, and faster than ever. I have attended lectures hoping to hear of a magical solution but to date, none has arisen. Stages of woe 1. Early spring (soil temps around 50 degrees). Tiny jumping worms hatch from cocoon encased eggs. How good is your eyesight? Those cocoons are 2-3 mm in diameter. The worms are also very small and easy to overlook as they blend in well with the soil and small twigs. The clitellum will be very faint. 2. Late spring/early summer IJW eat. Much like the very hungry caterpillar, they devour everything and will leave the soil devoid of nutrients and the ability to retain water. Worms are smallish and not as squirmy during this stage; don't assume the worms you see aren't IJW. (I KILL THEM ALL since earthworms aren't native either and do have negative effects on the ecosystem. Added bonus - they aren't reproducing at this time. See the video below, My Forest Has Worms.) These worms were collected in late August. Clicking on photos will open them up in a separate window. 3. Late summer Mature IJW reproduce. They are parthenogenic which means they can reproduce without a mate. It is not currently known how many each adult can lay but in laboratory settings, up to 30 cocoons with 2 eggs each have been observed. (UMASS). 4. HARD FREEZE (used to be in the fall but weather is unpredictable) Adult worms die. 5. Winter Cocoons wait until spring temperatures reach 50 degrees and will reach maturity in 60-90 days Fact Sheet for Homeowners Connecticut Ag Experimental Station IJW Fact Sheet Straight from the scientists: Video: Invasive Earthworms (Jumping Worms) Dr Josef Gorres Video: Invasive Jumping Worms in Field and Forest Dr. Annise Dobson Video: My Forest has Worms Discussion Facebook Group: Invasive Jumping Worms: Observation and Discussion Group HOW DO I GET RID OF THEM?

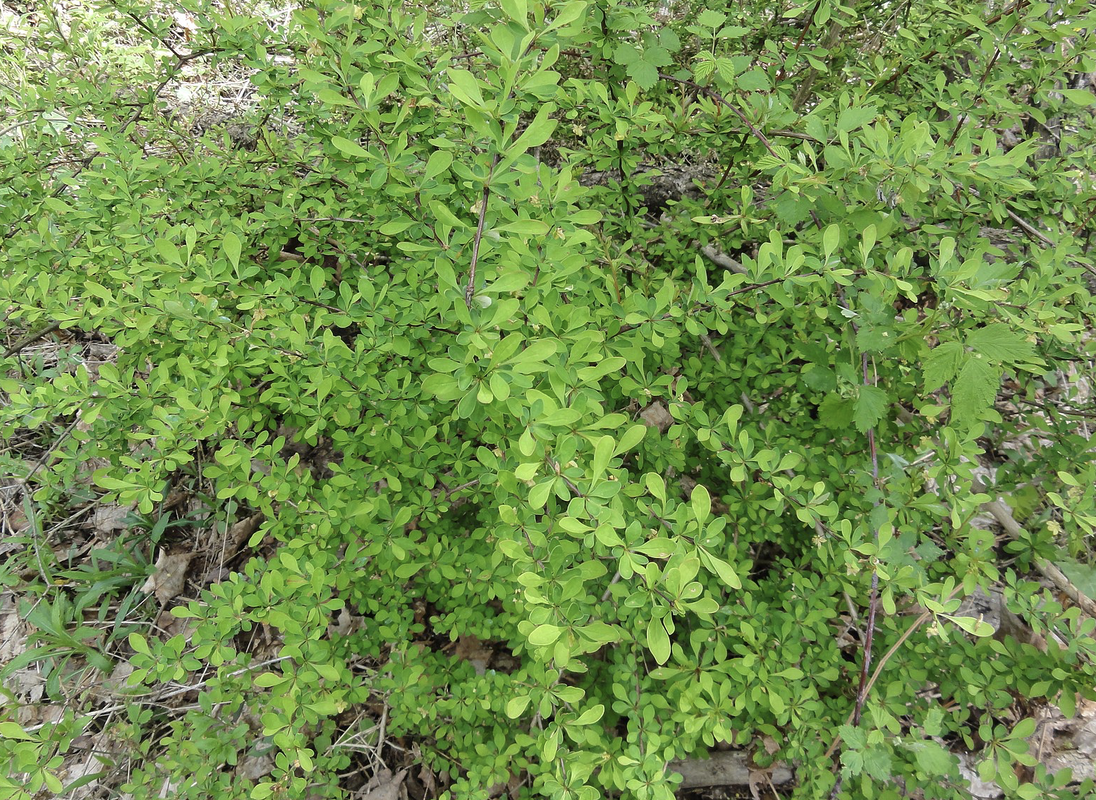

You will read or hear that a mustard pour, boiling/soapy water, and/or tea tree seed meal will kill the worms. Mustard pours do not, they irritate them and bring them to the surface. However, all of the above methods do have ecological consequences particularly for soft-bodied creatures like our native toads and salamanders. Tea tree seed has not been approved for this application but research is being done on its ecological impact. Others have said that their chickens and other birds will eat them and while this is somewhat true, IJW bioaccumulate heavy metals and toxins which impacts bird health. You can have your soil tested for toxins if you want to feed them to birds but it isn't recommended. Current best practices include: Hand-picking and dropping them into a bucket of soapy/vinegar water and disposing once they are dead. (I wait a day or two just to be sure then dump them in one small area away from my gardens.) They do emit an awful odor if left too long. I carry a baggie with me while hiking and will collect the worms when I find them. I'll dispose of later - either by drowning them in a bucket or leaving the bag in the sun. Solarizing the soil. Using CLEAR plastic to create a greenhouse effect, you can kill the eggs before they start to hatch by bringing the soil temperature up to 104 for three days (does not have to be consecutive). You want the soil to be heated to a depth of at least 4". DON'T FEED THEM. Forget the mulch and add more aggressive native plants. Most prairie/meadow plants can tolerate the conditions. If you do buy mulch, soil, or compost make sure that they are free of IJW (really difficult when the season starts) but you can ask if the materials have been solarized and what they have done to prevent infestation. BE WARY OF PLANT SALES Again, at the beginning of the season it is really difficult to know whether a pot has IJW or not. You can look for the castings. You could pull the plant out of the pot to see if there are tunnels created by IJW. Buy Bare Root Plants. It's mostly shrubs and trees that are sold bare root (without soil). If you do buy potted plants, bring them home, knock off all the soil(into a bag), rinse the roots. Solarize the bag of soil, then strain the water for solids and dispose in the trash. CLEAN your tools, equipment and shoes since cocoons could be present in the debris and could be transferred to other places. Report them There are many apps for you to use to report sightings of invasive species: IMapInvasives, EDD Maps, and iNaturalist Contributions help scientists understand the scope of the problem and develop management strategies. submitted by Lynne Warren Tick Season Lynne Warren, advanced Master Gardener, Goodwin Volunteer Let’s talk about Deer Ticks, Ixodes scapularis, (aka blacklegged ticks) the tiny blood-sucking parasites that can ruin a good night’s sleep when you subconsciously scratch and find that bulbous body attached to yours. If you’re like me, you’ll get it off as quickly as possible and regret that you didn’t use the tick key and now have part of the tick stuck in your skin. Then, you’ll spend an hour trying to dig it out, clean it up and wonder where you put the antibiotic cream. Sleep is now impossible because where there’s one, there has to be more and do I now have Lyme? What time does the pharmacy open?? Has your skin started to crawl just thinking about them?  From left to right: The blacklegged tick larva, nymph, adult female and adult male. When the blacklegged tick is in its nymph stage, the risk of transmission of Lyme disease is the greatest. Nymphs are tiny (less than 2 mm) and are difficult to see. From left to right: The blacklegged tick larva, nymph, adult female and adult male. When the blacklegged tick is in its nymph stage, the risk of transmission of Lyme disease is the greatest. Nymphs are tiny (less than 2 mm) and are difficult to see. Deer ticks can live in wooded areas, tall brush/grass, under leaves, under plants, around stone walls or piles of wood (basically anywhere small mammals or birds live). They thrive in moist environments. Deer ticks have a two-year life cycle and will eat three times, once at each stage of development: larvae (early summer), nymph (June/early July) and adult (early spring/late fall) Adult populations tend to peak in Apri/May and late October. What can you do to reduce your risk? I’ll give you my approach. The first thing I do every year is treat my pants, baseball hat, and shoes with permethrin. It’s available at hardware stores, big box stores, and online. Permethrin kills ticks and mites and will last through a few washes. (I will typically hang pants in the sun after wearing and dust them off to make the most of the treatment.) Most ticks will come from the ground or plants up to waist height, not from overhead. I personally will not wear khaki in the forest since I think it makes me look like a host animal (deer in particular). So, I buy dark brown, green pants or gray pants - I can still spot the ticks if they crawl on them but feel they give me camouflage. (not a scientific fact but based on my own experience). You need to plan ahead as the chemical needs to dry before wearing. I do not typically use any man-made chemicals but given the choice between Lyme disease or chemical, Permethrin will win every time. The next task is to do a tick drag. I take a light colored sheet and drag it through areas I’m going to work. On a “good” day, I’ll catch many ticks. (In scientific experiments tick dragging only managed to pick up 10-15% of the ticks present. So, an empty sheet doesn’t mean there aren’t any ticks.) If I catch some, I’ll pick them off the fabric and put them in a sealed plastic bag to dry out. Heat (130°+) and dessication kill them. They do not drown. If you want to squish them, use rocks, never your hands. Mulching 3 feet between the woods and your yard will help keep your lawn tick-free. It creates a hot, dry area ticks won’t like. Encouraging predators: ants, dragonflies, bugs, beetles, centipedes and spiders are the largest tick eating group. Oppossums, birds, frogs, toads, mice and shrews will also eat them. I know raking up leaves can help control the tick population but so many beneficial insects rely on them, I will not. Eradicate Japanese Barberry. This invasive shrub has dense foliage that allows the plant to retain high humidity (ticks need moist environments). Barberry also creates a nesting habitat for the white-footed mice which are the primary source of larval ticks’ first meal. It outcompetes our native plants (which help support the predators that eat the ticks) and is one of the first shrubs to green up in the spring. My approach to getting rid of barberry is to cut off it’s food (sun). I wait until the canopy starts to fill in (late spring). By then, the barberry will have used a fair amount of energy to leaf out. I’ll take loppers or a chain saw and cut it to the ground then PILE the cuttings on top of the crown. I may have to repeat this for larger shrubs but the goal is to never let it bloom and never let it see the light of day again. At the end of the day, do a full-body tick check. I may still find one in the middle of the night but it’s most likely because one of my pets decided to share.  Japanese Barberry, Berberis thunbergii. Photo Credit: R. A. Nonemacher Japanese Barberry, Berberis thunbergii. Photo Credit: R. A. Nonemacher If you have any questions, please share in the comments!

by Kathy Beaty, Goodwin Master Naturalist Intern, Level 1 Just after Thanksgiving, 2020, I reached out to the Great Meadows Conservation Trust in Wethersfield to seek permission to install my Critter Cam on their property. I am conducting an 8-month study observing and reporting wildlife for my Master Naturalist Certification research project. Jim Woodworth, Stewardship Chairman of the GMCT, quickly expressed interest in my project and offered to meet me at the Wood Parcel in Wethersfield, where there were telltale signs of recent beaver activity on surrounding trees. We met and walked the beautiful, forested trail near Beaver Brook (appropriately named) to an area clearly enjoyed by American beaver. There were numerous young aspen saplings cut and we were pretty optimistic that the installation of the Critter Cam would catch nighttime beaver activity. Beavers have thick dark brown fur and a stocky muscular body. Their hind feet are webbed for swimming and have a flat, hairless tail that about 12 – 16” long. A beaver can weigh between 30 and 65 lbs., and have brownish orange, sharp, prominent incisors that make quick work on any young saplings. Beavers are most active at dawn or dusk and they are much more active late fall preparing for winter, feeding on inner bark, twigs, leaves, and roots to build up extra fat to survive the cold months. They will also store a winter food pile of branches and sticks piled near their lodge so it can be accessed underwater. That afternoon, I positioned my Critter Cam in the spot where it was likely the beaver would return. Here's what happened. (Beaver in Wood Parcel, Great Meadow Conservation Trust, Wethersfield CT) In the span of 7 minutes, this hungry beaver gnawed off the Aspen sapling and started to move it to its lodge, somewhere by Beaver Brook, although Jim and I couldn’t find it. Beaver are semi-aquatic and live-in rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes so we knew it was just a matter of time before we found it. I left the camera on that site for several days and witnessed similar activity in the evening as it chewed and moved trees away, but still did not see the lodge. Then, in early January, Jim told me he thought he found it on the other side of the Wood Parcel approximately 125 yards away from the initial site. It was much harder to access and was near a wider area of the Beaver Brook near the road of Maple St, Wethersfield. We met again and gingerly navigated through the rough terrain where there was considerable activity and I once again positioned the camera on a tree anxious to discover what we’d see. (L) lower right of photo, beaver activity (R) lower right, tree completely cut by beaver This beaver took down a much larger tree in the brook in 10 minutes, and I was concerned that the next tree could be the one I installed with the Critter Cam. I knew I had to get down to Wood Parcel to retrieve my camera. Here’s what I found in the early morning:. I was able to get this footage just before it took its dive under the water. Beaver swimming in Beaver Brook by its lodge, Wethersfield CT So, there you have it; a fun little nature adventure visiting the habitat of the American beaver. They mate in late January to March, and produce a litter in May or early June. Who knows, maybe we can catch a glimpse of the beaver kits in the Spring.

submitted by Meaghan Rondeau, Naturalist Goodwin Conservation Center Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) In late June and early July in eastern Connecticut some of our most beautiful native wildlife starts to appear: monarch butterflies. Monarch butterflies are one of the most well-known and appreciated butterflies in the United States. Within the U.S. there are two regionally distinct groups of monarchs: the western monarchs and the eastern monarchs. They are the same species; the only difference is in their range. The two groups are split by the Rocky Mountains. Western monarchs breed west of the Rocky Mountains while eastern monarchs breed east of the Rocky Mountains (pretty easy to remember, right?). But that’s not all, the two groups overwinter in different locations as well. Monarchs are famous for their yearly migration to Mexico, but the eastern monarchs are actually the only group that travels to Mexico. Western monarchs overwinter in Southern California-- close to Mexico, but not quite over the border. Additionally, while monarchs are only native to the Americas, they have spread across the globe and now reside in many subtropical areas of Europe, Oceania, and Africa. Despite their shocking range, both western and eastern monarch populations are in a steep decline. While not yet on the endangered species list, there has been significant push in the last decade to have the species evaluated and given a protected status. Among the greatest threats to monarchs are habitat loss and climate change. The loss of milkweed habitats for caterpillars to grow on has been detrimental to the species. Monarch caterpillars only eat milkweeds, and while the U.S. does have many native milkweed species, they are commonly mowed down in both agricultural fields and on roadsides. Milkweed contains a toxic latex that can be poisonous to cattle if consumed in large enough amounts, so the fields where milkweed prefers to grow, are often systematically cleared of the plant for the protection of the cattle. And, along roadsides where the plants also flourish, roadside mowing and herbicides destroy valuable habitat. While protecting cattle and keeping roadsides clear is important, the destruction of habitat without providing safe growing space has led to the staggering decline of monarch butterflies. Climate change is another threat that monarchs, like most species, must face. Changing global temperatures and weather patterns disrupt the breeding and migration patterns of monarchs. Extreme weather can wipe out huge populations of monarch butterflies, caterpillars, and milkweed. And unseasonably cool or hot temperatures can cause mass die-offs of the delicate animals. Migration is vital to the life cycle of monarch butterflies. They breed in the northern parts of the U.S. but with the arrival of cool fall temperatures, they must journey south where they will be warm enough to survive the winter. The western population travels just along the west coast of North America, travelling north to breed and then south to overwinter. The eastern population breeds in the northeast U.S. and eastern Canada, then migrates to central Mexico. When we see monarchs appear in the early summer, they are returning from their tropical Mexican holiday. Right now, they are reproducing as they work their way north. A single butterfly does not make the whole north-bound Mexico to Canada journey, instead, four or five generations will take place as one genetic line travels up and down the coasts. Each generation grows from egg to butterfly, quickly reproduces, and then continues north. The growth process, from egg to adult, takes two weeks to a month depending on weather and temperature. The eggs take less than a week to hatch--if they aren’t eaten by predatory insects first-- and then the caterpillars will gorge themselves on milkweed, quickly growing from the size of your eyelash to your pinky finger. They go through five in-star phases, or sheds, during this process. When they reach this size, they find a safe place to hang from and form a delicate chrysalis. Over the next two weeks’ time they will transform into an adult butterfly. Once they emerge they dry off their wings and then get to work finding food and creating the next generation of monarchs. The reproducing adults live for just two to five weeks. At the end of the summer or beginning of fall, the last generation hatches. These late bloomers are the travelers of their family, traveling up to 3,000 miles back to the warmth of the Mexican mountains. They will live for up to nine months-- plenty of time to stay warm all winter and begin the journey north again to mate. It is important that the butterflies have plenty of nectar food sources one their journey to Mexico, because once they arrive they do not eat anymore until they leave in the spring. They survive off their body fat and water from dew. They are very inactive during their overwintering period and do not need additional food for energy. To help support monarchs, and other native pollinators, there are several things you can do. At your home, school, or business, consider planting a butterfly garden. For monarchs in particular, make sure to include at least one of our native milkweeds: common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), or butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa). Other plants that provide an excellent nectar source are: golden Alexanders (zizia aurea), wild bergamot (Monarda fistula), black-eyed Susans (rudbeckia hirta), coneflowers (Echinacea spp.), anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum), Joe-pye weed (Eupatorium maculatum), and goldenrods (Solidago spp.). Make sure that the plants you choose are appropriate for the location--if you need help, many options are available online or you can reach out to a local garden club or your local extension service. If you own or know of an area where healthy milkweed grows every year, that isn’t mowed or sprayed with pesticides or herbicides, consider creating a registered “Monarch Waystation” through Monarch Watch, a monarch conservation program. Not only are these great for monarchs, but they’re incredibly valuable in increasing public awareness about the importance of milkweed habitats for monarchs. If you are a farmer or maintain land where milkweed grows, consider looking into alternative maintenance methods that don’t involve removing milkweeds, or create new areas of milkweed to offset the loss and support migrating monarchs. And, if nothing else, be a monarch advocate. Spread the word about the importance of maintaining healthy milkweed and monarch habitats so that monarchs will continue to be a beautiful presence in Connecticut every year. Here are some helpful links with additional information: Monarch watch: https://www.monarchwatch.org/ Audubon tagging: https://www.ctaudubon.org/2019/09/tagging-monarchs/ Life cycle diagram: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/biology/index.shtml#:~:text=The%20monarch%20butterfly%2C%20like%20other,(chrysalis)%2C%20and%20adult. Monarch biology: https://monarchjointventure.org/monarch-biology/life-cycle/adult Weekly migration news: https://journeynorth.org/monarchs Monarch migration: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/Monarch_Butterfly/migration/index.shtml Milkweed and monarchs: https://www.nwf.org/Garden-for-Wildlife/About/Native-Plants/Milkweed Milkweed biology: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/asclepias_syriaca.shtml Milkweed biology 2: https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/cs_assy.pdf |

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed